Mapping diasporic rhythms

[Theme music fades in behind the narration]

[00:00:00] Deirdre Molloy: So I'm making it visible and it's a very useful way to organize rhythms, because Rhythms organize society, rhythms, organize social synchrony.

[00:00:12] OreOluwa: Welcome to Groovin’ Griot, a podcast about how we use dance to tell stories. I’m OreOluwa Badaki.

[00:00:18] Azsaneé: And I'm Azsaneé Truss. Let's get grooving.’

[Theme music plays at full volume]

[Theme music fades out as we transition to sounds of flipping through records}]

[00:00:48] Azsaneé: Today we're coming to you from a one of a kind spot.

[00:00:50] OreOluwa: We're at Sook Vinyl & Vintage, which is currently Philly's only black owned record store and is dedicated to the music and art of the black diaspora. We are listening to Khan Jamal right [00:01:00] now, which we were just introduced to by the founder of Sook.

[00:01:03] Rashid Amon: Uh, my name's Rashid Amon. We are a vintage black culture boutique. Everything in the shop's, at least 20 years old and reflective of Black culture. Um, we're very, very music forward. However, you could find books, ephemera, art, all types of stuff. Uh, centering Black culture here.

[00:01:20] Azsaneé: How much is this?

[00:01:21] Rashid Amon: Oh.

[00:01:22] Azsaneé: Or is it for sale and, yeah. Okay.

[00:01:25] OreOluwa: Which one are you getting?

[00:01:27] Azsaneé: One of the other ones

[00:01:28] OreOluwa: Nice. Cool.

[00:01:29] Azsaneé: 10, like, let me just. Start my cart.

[00:01:34] OreOluwa: Yeah, I'm definitely getting one of those.

[00:01:39] OreOluwa: Where do you get your, your magazines from? Same places as the records.

[00:01:43] Rashid Amon: Um, no.

[00:01:46] OreOluwa: Okay.

[00:01:47] Rashid Amon: I just keep my eyes open. I guess.

[00:01:49] OreOluwa: Yeah.

[00:01:50] Rashid Amon: I'm always looking for it. So after I, after I opened the shop, like stuff started coming to me.

[00:01:55] OreOluwa: Yeah.

[00:01:56] Rashid Amon: Call it my beacon. That's kind of why I deal with the overhead 'cause I [00:02:00] find way more stuff having a store than just being like… a person.

[00:02:04] OreOluwa: Yeah, 'cause the stuff knows it has a home to go to probably so.

[00:02:07] Rashid Amon: So a lot of, sometimes we get donations. A lot of people come and buy stuff. I mean, sell stuff to us, so.

[00:02:12] OreOluwa: Oh, that's dope.

[00:02:13] Rashid Amon: Um,

[Transition]

[00:02:15] OreOluwa: So we're here in a place that centers the rhythms of the African diaspora because today's episode is about how these rhythms travel across the diaspora.

[00:02:22] Azsaneé: That's right. A little while ago we got the chance to talk with Deidre Molloy, a dancer, ethnographer, and multimedia artist who has been mapping how rhythms and dances travel across the Black Atlantic.

[00:02:32] OreOluwa: Deidre is currently a doctoral candidate in a dual degree program at the University College Cork in Ireland and the University of Toulouse in France. She's completing an Arts Practice Research Thesis, which means she makes art as part of her thesis.

[00:02:45] Azsaneé: Very much in line with the multimodal scholarship we talk about constantly on the show.

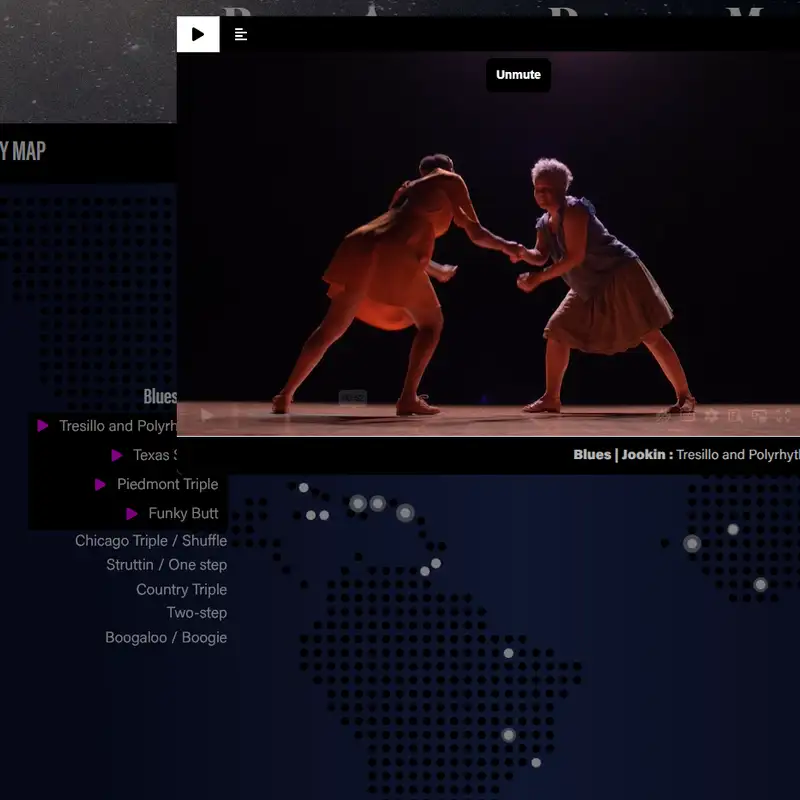

[00:02:49] OreOluwa: Very much so. And for Deidre's project, she's building an interactive digital map that highlights rhythms and dances across the black Atlantic. She's called it the Unity Map, and in addition [00:03:00] to the web-based map, she has made films, choreographed performances and curated exhibits and installations connected to the project.

[00:03:07] Azsaneé: We were really excited to get the chance to sit down and talk with her about this work. She started by telling us a bit about her background.

Early dance experiences

[00:03:14] Deirdre Molloy: I grew up in Ireland and Barbados and my memories of dance in Barbados, I mean, I don't have, I don't have memories of dance from Barbados really 'cause I left when I was eight. But something, maybe something from the Caribbean came with me because I became the person who just dances all the time, even though no one around me was really doing that.

[00:03:30] And so I didn't have much of a dance community. And so I came to learn dance codes quite late in life, which was say around, uh, 2000. And so 2008 I started really picking up, uh, dance hall. Like I started to, to see dancers, dancehall dancers, who I wanted to be like them, dancehall Kings, dancehall, Queens, you know, in the party on the stage.

[00:03:53] Wanted to be like them, wanted to know, know something about how to move like them. And so I began those classes back then. [00:04:00] And, uh, and then I got into blues partner dancing, so blues dancing and from blues dancing into Lindy Hop and from those two partner dances into whatever partner dance that I could do.

[00:04:12] You know, if you're doing partner dance, I'm in, I'm there, I'm in, I do Brazilian Forro, all kinds of stuff. Uh, um, Kizomba. But mainly the ones that I was, was doing were, were the ones that I've made main, mainly maintained my practice in our Blues and, um, West African now and Dancehall.

[00:04:35] Azsaneé: I found this album, uh, Lucille from BB King, which makes me think a lot about my grandfather. He still listened to quite a bit of BB King. Um, but it's relevant to this conversation because, um, Deidre does a bit of blues dancing.[00:04:49]That's one of her. You know, primary partner dance genres.

Finding roots in the Blues community

[00:04:52] Deirdre Molloy: And also the community, the blues community itself became interested in the history of the dance because there was a [00:05:00] movement, uh, from various, from, from, from people in the most memorably, I guess this started to happen in around 2020.

[00:05:09] There was Collective Voices for Change, which was led by Marie N’Diaye, um, in Europe. This started a series of, uh, conferences about Lindy Hop as a culture with, you know, culture bearers. Um, talking about the culture to educate a mostly White dance, um, community about these dances as a culture. And so I guess the atmosphere of interest in dance history and my own search, consideration of my own identity, I began to realize that living in Australia, even though I was doing all these Black dances, I felt I was culturally isolated.

[00:05:47] I was culturally isolated just by living there, by being very far from the Caribbean where my mom is from, by being very far from the US where I was born, by just being very far from Black cultures. That was my experience. [00:06:00] And so I turned towards this culture and I decided to take it very seriously. Uh, and you know, I, I already, by the time I started to do that, already had, you know, a master's degree in multimedia.

[00:06:16] I'd been having this career in science communication, but I just, I had this realization, or I had this, this…, like I came to, to see Black dances as my cultural heritage and a cultural heritage that wasn't being recognized as a cultural heritage. So I wanted to tell that story and deciding to tell that story.

[00:06:39] Uh, there was so many, so many steps that led me there.

[00:06:47] Azsaneé: Deidra shared that her path to creating the unity map and reclaiming some of her cultural heritage included taking a year off of work to travel around the world, studying blues partner dancing and other diasporic dances,[00:06:57] eventually quitting her job in Australia to study [00:07:00] these topics full time, tearing her ACL, recovering her movement practice, getting a master's in dance ethnography, and more.

[00:07:06] OreOluwa: Golly, that's, that's not an easy path, but it was worth it. Deirdre started to notice something about the dances and rhythms she was studying.

Unity of dance and music

[00:07:14] Deirdre Molloy: West African dance has this unity of image, say like, for example, a mask or a costume or a, whatever you, you know, the ceremony calls for. You have this imagery, you have this, uh, rhythm that's super important and you have a dance that goes with it.

[00:07:33] And I became aware of this also in Blues around the same time as I was experiencing it in, even before I experienced this in, in West African music. In Blues dances, uh, we have what's called idioms. So you have different basic steps or basic movement for, let's say a walk-in base ballrooming type of step or space.

[00:07:57] So also the space affects how you [00:08:00] dance. So you could have ballrooming and you have jukin, and the ukin happen in the smaller spaces. And the dance steps can, are, you know, are, are very closely linked with the rhythm. So let's say you have a Texas shuffle or you have uh, just Chicago, Chicago Shuffle can give you a Chicago triple step, or you have a one step type of marching type of rhythm.[00:08:21] We'll give you another type of step. So I became very aware of, of all of these, uh, unity, the unity of dance and rhythm and image that I wanted to communicate because I could see in the European context that this wasn't really a thing in contemporary dance, uh, that it wasn't so strong in these other cultures.

[00:08:41] Azsaneé: The observations Dierdre was making informed how she documented and analyzed data as part of her research process.

Research technique

[00:08:48] Deirdre Molloy: So I would say the research, the research techniques are, , all about communicating this unity of dance and music and [00:09:00] recognizing rhythm as a unit of knowledge.

[00:09:04]So I recorded this rhythm in a studio setting with a culture bearer in France, who lives in France, and I also recorded it in his village as a ritual.

[00:09:11] Now, this was when, when I staged it with him, uh, when I staged this, uh, Abodan rhythm with Clément Assemian, he's the one who chose the rhythm. I said I wanted to record, you know, a rhythm from his ancestral heritage, and he chose this rhythm.

[00:09:28] Um, and the rhythm that he chose is one that really translates as a call to gather. It's a call to gather. It brings the community together. It's, it's a moment of being together and that it's danced at weddings and funerals. Um, so it's really about that unity, uh, and social synchrony and physical synchrony.

[00:09:51] So that's one example of, of a rhythm that's portable that he can present here in France, but that's also a living [00:10:00] ritual. From his village, uh, of Aby in Ivory Coast.

[00:10:05] There'll be a set of steps that, um, Professor Ofosuwa Abiola calls “root steps”. Um, you could call them, you know, basic steps. They're not basic. That's the thing though. They're quite complex sometimes 'cause they're, they're connected to these complex rhythms. Those root steps connected to the rhythm are coated movement.

[00:10:25] So the step that people are doing, everyone's basically doing the same step, but they can also bring their own unique flavor to it, which is a very Black thing to do.

[00:10:37] OreOluwa: Dere mentioned Dr. Ofosuwa Abiola, who we actually got a chance to talk to last season.

[00:10:43] Azsaneé: That's right. That was episode three I think. I think

[00:10:45] OreOluwa: I think it was. Yeah.

[00:10:46] Azsaneé: Feel free to pause here if you want to go and take a listen. We'll wait.

[00:10:50] OreOluwa: I mean we won't, but you know, this track will, so take your time

[00:10:53] Azsaneé: And in case you do just want a quick summary instead, [00:10:56] we had a great conversation with Dr. Abiola about the history of African dance [00:11:00] systems. It's cool to see how her work is informing projects like Deidre's Unity Map. Dierdre talked about the methodology she is developing that centers on the codes in the root steps that Dr.[00:11:10] Abiola’s work helps to unpack.

Rhythm Codes

[00:11:13] Deirdre Molloy: and the, at the core of the, at the core of the methodology is the theory of rhythm codes, a rhythm code is the embodied knowledge you need to belong.

[00:11:23]And so it's based on, um, it's based on my background. I guess my very first degree is in psychology. And in psychology I learned about memory. Um, and one of the very basic things that you learn about memory in psychology is that you have declarative memory and you have muscle memory. Now, you could call it muscle memory.

[00:11:50] You could call it procedural memory. It's also known as implicit memory, but declarative memory is the kind of memory that you can talk about easily. So I played golf [00:12:00] yesterday. That's declarative memory. It's, it's something that you can write down and say, but can you say how you swing your golf club and hit the ball and get it to go a certain place?

[00:12:11] That's not something you talk about so much. So it's what you might call implicit memory or muscle memory. 'cause it's the skill that you've learned to execute that thing. And same with riding a bike, uh, learning to play an instrument. Um, that's the basis of, that's, that's the, an underlying assumption.

[00:12:28] That's the kind of scientific premise from which I am looking at this embodied knowledge. And, uh, it, it really helps me to organize the data. So the idea of rhythm codes, rhythms being the embodied knowledge you need to belong comes from, as I said, this, uh, concept of muscle memory or implicit memory or procedural memory, which is really all the same thing.

[00:12:53] There's different kinds of implicit memory, but, but muscle memory is the one that's most relevant to us, I guess as dancers. We can think about that. [00:13:00] And, um, and so you've got muscle memory and this idea of accessing belonging because. This began for me personally as a kind of, um, it became an identity narrative that I needed to, to create, you know, um, that I felt that, as I said, these dances are intangible heritage.

[00:13:25] Uh, but when I say rhythm code, I mean a rhythm code that, as I say, it gives access to a circle of belonging, like, uh, Capoeira or, um, a hip hop cipher or um, uh, DC hand dancing.

[00:13:46]: These are all codes that give you access to a space of belonging. And also to an identity. And like for example, the identity is very often connected to the place that you're, like DC hand dancing. It's named after dc [00:14:00] um, Memphis Jookin named after Memphis. These are all ways that we identify with our music and dance…in a geographical sense too.

[00:14:11] Azsaneé: All right, so now we are getting more into the mapping aspect of the unity map. Deidre just shared why the geography of where dances get coded matters. But before we dive deeper into this topic, I think it's time to take a little movement break.

Movement Break

[00:14:24] OreOluwa: Great! So for this movement break, we're taking you to a place that is famous for how it has preserved and innovated on black rhythm codes: [00:14:30] New Orleans. Widely recognized as the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans was a cultural hotspot for African diasporic rhythm. And Dan. The sound collage you're about to hear is from my trip there for a conference a couple months ago where it got just a small taste of some of its dizzyingly dynamic cultural heritage.[00:14:47] Part of the sound collage is from an event at Congo Square, a place that has been crucial to black rhythm code since at least the mid 18th century.

[00:14:54] [Sound collage from Congo Square in New Orleans –Congo Square Preservation Society]

[00:18:14] Azsaneé: Welcome back. Keep the sounds and rhythms of New Orleans close As Deidre will talk a bit about this later on in the interview. But first, she shares more on how the movement and migration patterns of dances and the sociopolitical tides in forming these patterns made mapping a compelling topic to delve into.

Importance of mapping

[00:18:31] Deirdre Molloy: The Great Migration influenced my, um, visual approach because I had heard about these different, um, blues idioms, so I'd heard about Piedmont, Chicago Triple, um, uh, Texas Shuffle.

[00:18:46] The Texas Shuffle is one that. Was affected by the Great Migration. It's known as a Texas shuffle, even though it was mainly danced in LA or around the West Coast. And so in order to make this clear for myself and also to make it [00:19:00] clear for an audience, I wanted to visualize it, I wanted to see this migration.

[00:19:05] Um, so, so yeah, so as to understand and visualize it for myself. Um, and then as I was looking for maps, 'cause that's what you have to do, like when, when you're doing graphic design, it's, there's an aspect of my design called image research. So you're looking for ways to tell this story visually. You're looking through visual archives, not just text archives.

[00:19:28] Deirdre Molloy: And um, and at some point when I was looking for maps, I came across this map called the Mercator Map of the World United. It was published in the 19 at the, around 1944, I think, around the time of World War I or World War II, sorry.

[00:19:45] Deirdre Molloy: So it was a World War II timing of it. But the map is all about how, how technology is gonna bring peace to the world. That's why it's called the Mercator Map of the World United. I think the full [00:20:00] title is the Mercator Map of the World United. Uh, something about paths to permanent peace and it's centered on the Atlantic, and it shows boat crossings and it shows a postman.

[00:20:13] It shows planes. It's celebrating radio, planes, postal system. All these communications that we take for granted now are celebrated in the map as new technology that will bring the world together and bring us all peace and happiness. But the boat journeys that are shown are shown as a progression from slower boat travel to faster boat travel.

[00:20:38] And there's no slave ships in there. The first ship is the Mayflower, and then the fastest ship, I can't remember is, might be the Cunard Line or something. Right. So there's a lot of historic erasure going on, and I started to feel that this was needed to be addressed because even though the Mercator map was made in the forties or fifties and is a historical [00:21:00] object that not many people know about, the narrative of the Mercator map is that the UK and the USA are the center of the world, are the harbinger of future peace.

[00:21:10] They're the center of the world's technologies. And, um, and that in Africa they've got some drums. You can see some drum. You can see a drum in Africa, you see, you can see some camels, you can see some men carrying stuff. But you can't see anything, like, there's no concept of, of African culture there in this map.

[00:21:31] Uh, it's all about the UK and the USA being harbinger of, you know, the bringers of world peace. That's what the map is telling us. And that's the, that's the dominant narrative. The dominant narrative i,s the USA is the world's policemen. Europe is the place of civilization and culture and technology. This is the story that we're being told in the map and, uh, and at the same time completely erasing the slave trade.

[00:21:54] So I just felt, I need to do something about this. And, um, [00:22:00] and so, so, so it was a, just a, a chance… I had this idea of starting to map rhythms from, as a kind of an answer to the Mercator map.

[00:22:09] OreOluwa: This history of the Mercator Maps is super interesting.

[00:22:11] Azsaneé: Yeah. So the CliffNotes on that are that in the 16th century, a Flemish guy named Gerardus Mercator supposedly came up with a new way to represent navigation lines on a map

[00:22:22] OreOluwa: Among other things, these new projections made places farther away from the equator, like what came to be known as Europe and the US look much bigger than they actually are. How convenient.

[00:22:31] Azsaneé: Very, uh, it took a while for this new projection to catch on, but by the 19th century it was a standard in the cartography and mapmaking industries.

[00:22:40] OreOluwa: Fun fact; Philly was reportedly the center of American Map publishing back then. [00:22:45] Go Birds!

[00:22:47] Azsaneé: Um, anyway, the 1944 Mercator Map of the World United is part of this story. And now Dierdre's Unity Map is adding a crucial and critical perspective to this cardiographic narrative.

[00:22:58] OreOluwa: Because maps aren't [00:23:00] neutral nor objective, [00:23:00] how we represent space and movement says a lot about how we organize power.

Mapping and naming rhythms

[00:23:05] Deirdre Molloy: When I first was conducting my research interviews in 2021, uh, one of the first people I interviewed was Karamako Kone, who's a.

[00:23:13] griot, but he's from a family of, of, um, metalsmiths and, um, in Manding culture. And when I, I asked him, I can't remember what specific question I asked him, but he said that he identified, yeah, I think, yeah, we were talking about where he comes from and he said that he identifies more with the Manding Empire than with Ivory Coast where he was born.

[00:23:38] But he also said, said that he'd seen some writing about dance, about rhythms, but that, that it was a mistake to name the rhythms after countries like Ivory Coast or Guinea.

[00:23:53] He said that would be a mistake. They belong really to Manding culture. And, and so [00:24:00] that was just a clue. He's like, that was just a clue to like, ah, this is how you do it. This is how, this is how rhythms are organ, organized. They're not organized by Guinea, Senegal, uh, Burkina Faso. Uh, that's not how they're organized.

[00:24:15] Deirdre Molloy: They're organized in an ancestral way that predates these nation states that you find on maps. And so what else is being invisibilized here? What is being invisibilized here is West African kingdoms, empires, and history.

[00:24:33] Azsaneé: Deidre continued to find resources that helped her to trace how rhythm codes have developed across time and space and to make visible important insights around social dynamics.

Rhythm and rationality

[00:24:42] Deirdre Molloy: So I'm making it visible and it's a very useful way to organize rhythms, because rhythms organize society, rhythms, organize social synchrony. This is another idea that's in my research that comes from, um, uh, a [00:25:00] researcher called Michael Chwe.

[00:25:01] He has a book called Rational Ritual, and this book, Rational Ritual, helped me to understand that. Ritual solves problems of social organization. So ritual is used to synchronize and it, that specifically ritual is used to synchronize social perspectives or understandings.

[00:25:24] Of space and time and those understandings, he calls common knowledge. So rituals create common knowledge, and that led me to thinking about, well, rhythms create common knowledge, but they also synchronize time and space very precisely and very socially.

[00:25:43] That helped to confirm for me why it is that these rhythms are rational, uh, contrary to how they've often been portrayed in ethnography or general dominant narratives that, that, that, you know, music has [00:26:00] somehow just emotional or irrational or wild or savage.

[00:26:03] So you've got your rhythm knowledge, I'm trying to visualize rhythm knowledge in space and time, which leads me to make maps

[00:26:11] OreOluwa: In addition to the various rhythms she has located on the unity map, Deidre has been diligently tracing one particular rhythm called Tresillo, for which New Orleans plays an important role in its popularity.

[00:26:21] Deidre just published an article about this called “A Journey Through the Unity Atlantic Rhythm Map”, and we'll link to it in our show notes. She shared a little bit about her research tresillo during our conversation.

Tracing Tresillo

[00:26:33] Deirdre Molloy: So this one rhythm that's been traced by musicologists, as I said, is tresillo, and it's super popular, like it's now across all kinds of popular music. Um, but uh, you can see it very strongly in, uh, hear it very strongly and see it dance in different ways in both profane and sacred dances. Um, [00:27:00] and, uh, I think what really changes as well is the story and the image.

[00:27:06] So I think in, in the Americas we have, we have imagery that's much more influenced by the Bible, and our storytelling is influenced by the Bible. Our lyrics are influenced by the Bible, uh, and also by trauma and by. Plantation life and by port life you like. I mean, I think we all, we all have this concept of the plantation as part of slavery, but I think something that was very important in music was ports.

[00:27:36] So the Port of Buenos Aires, the Port of New Orleans, these ports had, um, a culture of prostitution and kind of gambling and good times, which creates a whole culture of music that goes with it, if you like. And a kind of a melting pot of, I guess Black, [00:28:00] like, you know, af African influences, Sicilian influences, uh, those biblical influences are there.

[00:28:06] Um, and then the values change. So the values could be something more about hustling, let's say, than worshiping an ancestor explicitly working worship, worshiping ancestor. So while you do have ancestor dances in the Americas, like, um, there are dances, that, that honor ancestors. I think the ring shout is one of them.

[00:28:28] You also have different values that, you know, you have these values of surviving in this capitalist society of, you know, making money and, you know, uh, hustling and, you know, having a good time drinking guns. Guns are a really big image in the, in, in, in the art. Like guns are a very strong image. For example, in dancehall, reggae in blues, you have this image that comes to me, I think that I noticed in blues because [00:29:00] I also have that Caribbean connection, which is the word jook.

[00:29:03] Deirdre Molloy: The word jook means to stab or gouge or penetrate. And it's, also means it's used to, it's a very violent word, but I think it's been transformed into a kind of ple, like it's jooks were pleasure houses also so Zora Neal Hurston describes the jook as a Black pleasure house. She says that the way the Black, the Black way of singing is known as Jukin, Black Singing and dancing is known as jukin.

[00:29:30] In her time in the 1930s when Zo, Zora Neil Hurston was visiting the jooks, this is what she's writing about is the, the fun that was had in the jooks. But that word in the Caribbean, it's meaning still is to gouge or stab. That's the meaning of it still in the Caribbean. So I feel like there's been a transformation that's happened maybe through music, um, and through dance and through owning something and through reclaiming our bodies.[00:29:58] I, I guess that may be a way to [00:30:00] look at it. Um, yeah.

[00:30:03] Azsaneé: So to round out the conversation, we asked Deidre the same question we ask all of our guests. What are you groovin’ to these days?

What are you groovin to?

[00:30:10] Deirdre Molloy: I guess, is the music that I'm still studying, which is there's a rhythm called Didadi from the Manding culture.

[00:30:18] And I didn't say it right away 'cause it might not be that easy to find, but it means sweet like honey and it's got a very complex rhythm and, uh, I mean complex to, to dance to. Um, so didadi and then on Sunday I was dancing to another Manding rhythm called Sunu. Um, so it's the Manding rhythms. And then when I wanna warm up, I'll put on some hip hop.

[00:30:41] Deirdre Molloy: Um, like, uh, there's a tune by Erick Sermon called “Music”, which has a Marvin Gaye sample, and it's gorgeous and I love warming up to that. Uh, yeah, just a, just, just a bit of hip hop always gets me in a good mood.

[Theme music fades in for credits]

[Music plays]

[Music is lowered behind the credits]

[00:31:08] OreOluwa: This episode of Groovin’ Griot was produced and edited by me, OreOluwa Badaki and my co-host, Azsaneé:Truss.[00:31:15] Our theme music is Unrest by ELPHNT and can be found on directory.audio.

[00:31:20] Azsanee: ou can follow us at Groovin’ Griot and email us at groovingriot@gmail.com. Groovin’ Griot is part of the network of podcasts supported by the Digital Futures Institute at Teachers College Columbia University, for another great show from the DFI network,[00:31:34]] check out the Curriculum Encounters podcast, which is about exploring knowledge wherever you find it.

[00:31:39] OreOluwa: Co-host Dr. Jackie Simmons and Dr. Sarah Gerth van den Berg [00:31:41] invite listeners alongside as they explore different spaces and consider how curriculum is a social, spatial and embodied process. It's a great sensory experience, so take a listen. We'll link to it in our show notes.

[00:31:54] Azsanee: That's all for now. Thanks for grooving with us.

[Theme Music fades out]

[00:31:58] *BLOOPERS*